Many people believe you must persuade the majority in order for change to occur. This is a myth. Instead, leaders should focus their efforts on a small but influential subgroup known as opinion leaders to get a new idea adopted.

[The post below is an excerpt from my book, Safety WALK Safety TALK ].

We accept change at different rates

Everett Rogers originally published his theory on the Diffusion of Innovations in 1962. It is a theory that seeks to explain how, why, and at what rate new ideas and technology spread through cultures. The book (now in its fifth edition) says diffusion is the process by which an innovation is communicated through certain channels over time among the members of a social system. The innovation or idea must be widely adopted in order to self-sustain.

In his book, Dr. Rogers tells a fascinating story of how he was prompted very early in his career to study how new ideas were adopted by the masses.

Immediately after graduating with a Ph.D. in sociology, Dr. Rogers accepted a job working with an agricultural extension service in Iowa. His primary responsibility was to work with the local farmers and encourage them to use newly developed varieties of corn which were proven in field tests to produce crops with higher yields, as well as being more disease-resistant. As a result, these strains of corn were more profitable than the current varieties.

Unfortunately, Dr. Rogers quickly learned he couldn’t connect with the farmers. He was a college-educated young man who had never plowed a field or planted corn. All his academic knowledge didn’t mean anything to the farmers. He lacked credibility.

He realized he needed to convince at least one farmer to try one of the new strains. That way, he reasoned, once this crop was proven to have higher yields, all the other farmers would follow suit and adopt the new innovation in corn seed.

After a while Rogers persuaded a farmer to try one of the new strains. There was one wrinkle, however. This farmer was unlike his neighbors in many regards. He drove a Cadillac, not a pickup truck. He wore Bermuda shorts, not jeans or overalls. Basically he was a social outcast in the farmer community. Nevertheless this fellow planted the corn and indeed enjoyed record yields that harvest season.

Yet no one followed his lead and adopted the new higher yield strains of corn. The reason: this renegade farmer wasn’t one of them. You can almost hear the other farmers muttering, “There’s no way I’m going to plant the same corn as that weird guy who calls himself a farmer. I don’t care what the yield is!”

This experience is what launched Rogers’ research into explaining why some ideas are adopted while others are not. He also set out to discover why certain individuals have more influence in encouraging people to accept an innovation or new idea than others. Rogers looked at research from over 500 diffusion studies across a number of fields: anthropology, sociology, technology, and education.

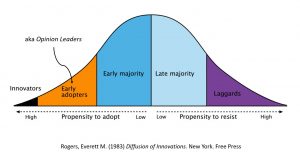

Rogers’ theory says within the rate of adoption there is a point at which an innovation or idea reaches critical mass. The people in any social system who are exposed to the new idea can be placed in segments depending upon their willingness to adopt the new idea or accept change. Rogers named five categories of “adopters”: Innovators, Early Adopters, Early Majority, Late Majority, and Laggards.

Don’t try to persuade the majority

Dr. Rogers submits there is a primary group you should focus on if you want to get a new idea adopted or to make change happen. It is not the Early Majority or Late Majority (the 2/3 of the population in the center of the adoption curve). Obviously it is not the Laggards. As the name implies, they are the last to accept anything new and will do so only as a final option.

But here is the surprising part. It is not the Innovators either. Even though these people are the first to try something new, they tend to be social outliers who generally do not have strong influence on their peers. (The farmer in the Bermuda shorts fits into this group). Plus true Innovators only make up 2% – 3% of the organization.

Rogers claims the real power brokers are the Early Adopters (Opinion Leaders). This group (about 13.5% of the population) is open to new ideas. But the key attribute that makes them valuable as agents of change is they are respected by a large number of their peers. They are also held in high regard by many people; therefore, they are socially connected to the network of the organization.

It is clear sustainable change can only happen if the Opinion Leaders can be persuaded to join the cause. If this group can be enlisted, you have the opportunity to reach a tipping point where the rest of the organization will follow their lead and adopt the change.

Opinion Leaders are the key to any change effort and are powerful influencers. Whether you enlist them or not, they will give your ideas either a thumbs up or thumbs down. And since they are respected and connected, they will exert their widely felt influence and decide whether (and at what rate) change will happen.

Identifying Opinion Leaders

Now that we know these people are critical to our plans to implement any major change, how do we identify them?

Since Opinion Leaders are employees who are among the most admired and connected to others, you probably know who they are if you have been in the organization for a number of years. You can validate your own view by simply asking people from across the organization to make a list of the employees who they believe are the most influential and respected. One question you may ask when soliciting these names is, “If you were to go to just two or three persons for advice on a problem you are having, who would you approach?” Then gather the lists and write down those who are named most frequently. These are opinion leaders.

It is important to note an opinion leader can be influential with their peers in either a positive or a negative way. In addition, don’t presume these people have some kind of formal authority. Many are informal leaders with no direct authority.

Opinion Leaders can tip the scales

I observed first-hand how this critical group of employees were difference makers.

After a number of near miss events involving pedestrians and forklifts, a large warehouse and shipping facility decided to implement an across-the-board policy which required everyone to wear high visibility vests everywhere except the office areas. The leadership communicated this policy to all the employees in a series of meetings. The general response was not positive. Quite a few people grumbled about the new safety vest requirement and cited numerous (weak) excuses why some employees should be exempt from this new policy.

The facility manager was taken aback by what he heard in these meetings. The policy was not negotiable. It was clearly the right thing to do. He had hoped more people would have accepted this new policy strictly on its merits of reducing risk. He decided to enlist some help to enable this change.

The leadership team had a fairly good idea who the Opinion Leaders were within the facility. They cross-checked their own lists with the supervisors on each shift to make sure they did not miss anyone. The Opinion Leaders were invited to a meeting where the management team outlined the reason for the new policy. They explained that requiring everyone to wear high-visibility vests was a simple but effective way to reduce the likelihood of a forklift operator inadvertently colliding with a pedestrian because they were not visible at times when walking on the warehouse floor. The facility manager closed by asking this group, “Can you help?”

Interestingly it became obvious in this meeting there were Opinion Leaders within the Opinion Leaders! You could see everyone’s head turn toward John before anyone spoke. John was not a union officer. He had no formal authority. He was actually soft-spoken. But he had been at the facility since it had opened over 30 years ago. And he commanded respect.

John cleared his throat and said, “I’ve seen my share of close calls when it comes to forklifts and people. A buddy of mine had his toes run over a number of years back, but his steel toes saved him. Why wouldn’t we want to do this? Seems reasonable to me.”

And with this endorsement, the others nodded their heads in agreement. The policy was put in place two weeks later, with minimal fanfare. Within a month, vests were as common as safety glasses within the facility.

Conclusion

What predicts whether an innovation / idea / change is widely accepted (or not) is whether the Opinion Leaders embrace it. Why? They are socially connected and respected. The rest of the population will not adopt the new practices until the Opinion Leaders do.

References

Galloway, David Allan. (2019). Safety WALK Safety TALK. How small changes in what you THINK, SAY, and DO shape your safety culture. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform (Kindle Direct Publishing).

Rogers, Everett M. (1983). Diffusion of Innovations. New York: Free Press.

Gladwell, Malcolm (2002). The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference. Little, Brown, and Company.

Patterson, Grenny, Maxfield, McMillan, & Switzler. Influencer. The Power to Change Anything. McGraw-Hill. 2008.