Greg was running late.

He glanced at the clock on the dashboard of his truck. His son, Travis, was the starting pitcher today for his high school team. Travis had traveled with the rest of his team to the field and he was currently completing the last of his warmup pitches. Greg’s wife was going to meet him at the game which was scheduled to start in five minutes. Yet he was still fifteen minutes away from the ball field.

As Greg’s truck crested a small rise on the two-lane road, he spotted a tractor ahead pulling a cultivator. Greg braked hard and slowed to 20 mph, slamming his hands on the steering wheel in frustration. Another hill loomed in the distance. Greg eased the truck into the other lane numerous times, looking for an opportunity to pass the farm vehicle, which blocked his view. Each time, he retreated behind the tractor as a car approached from the opposite direction and passed by. Finally, Greg saw an opening. Ignoring the double-yellow line, he steered his truck around the lumbering farm equipment and quickly accelerated.

Greg didn’t see the oncoming vehicle. It was obscured by a small rise in the road. The last thing Greg remembered on that fateful day was swerving to the left. He watched in what seemed like slow-motion as fence posts were clipped by his front bumper, each one splintering like a matchstick before disappearing over the roof of the truck. At the end of the fence line stood a large locust tree…

Meanwhile, Travis had pitched several innings and was doing well. That’s why Travis was surprised when his coach came to the mound in the middle of the third inning. The coach asked for the ball and told Travis to go see his mother who was sitting in the stands behind the dugout. She was wiping tears from her cheeks while pressing a cell phone to her ear…

How a Future-Looking Mindset Impacts Current Actions

- Personal Finance

Psychologists have long recognized that mindset can be a significant factor in determining outcomes. In other words, envisioning a positive future is often key to an individual achieving success. There are many citations of this phenomenon in the fields of sports and business. This concept has even been shown to be a contributor to certain behavioral aspects of personal finance.

Sarah Newcomb, a behavioral economist, investigated saving habits as they relate to someone’s mindset about their future. Newcomb conducted a survey of several hundred U.S. residents and asked them questions about how they envisioned their future and their personal savings. The results were quite revealing.

- Those who were living “in-the-moment” and looked ahead less than a year had saved less than $20,000.

- Those who looked about 3 to 5 years ahead had saved about $80,000.

- The people who had thought about their financial lives 20 years hence had saved over $400,000.

An important point: These findings on the time-horizon effect on personal finances were significant for people of different incomes, ages, education levels, and genders. “Time-horizon” had a greater impact on saving than any other demographic factor. Or as Newcomb summarizes it, “Income matters. But mindset matters more.”

- Personal Safety

Can a person’s mindset about their future be a factor in whether they take risks?

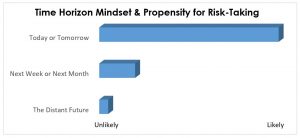

We can use the personal finance example above to construct a model for the likelihood of risk-taking as a function of how far in the future a person has either (1) set specific goals they want to achieve or (2) imagined experiences they want to have. It may look like this:

A person who envisions an entire career where they work injury-free is likely to achieve that outcome. Their actions are consistent with safe work habits. They are unlikely to consciously take an unnecessary risk.

On the other hand, a person who is only working day-to-day is much more likely to be hurt. Their actions and behaviors reflect a casual view about safety. They are more likely to have a propensity to take risks.

Unfortunately, a surprising number of people take a short-term view when it comes to their safety. They work one day or one week at a time – and their belief is that being injured (although not seriously) is somewhat inevitable. I have administered a safety culture survey to thousands of employees. One of the survey questions is, “How confident are you that you are able to work injury-free?” Overall, about 1 in 5 survey respondents indicate that they are not confident that they can work without getting hurt.

You cannot ignore it when 20% (or more) of your workforce hold this kind of viewpoint. Compared to their co-workers, these employees are more likely to be injured because of a self-fulfilling prophecy. What can you do to change the perception of these employees? One strategy is to reduce their potential risk-taking by encouraging them to think about their future.

- Personal Perspective

If you have an employee who has a casual view when it comes to safety, you may need to help them change their perspective. Make it personal. Here are several ways that I have used. All of them include pointed questions.

You really enjoy (fill in the blank with a hobby, sport, or interest), right? What would it be like if you weren’t able to do this in the future because of a workplace injury?

Do you have kids/grandkids? Have you considered what it might be like if you were severely injured (or worse) and didn’t get to see them grow up, spend time with them, or have a chance to observe their activities in school?

If your (brother/sister/son/daughter) were working here and you were training them to do this job, how would you instruct them to do it so they would never be hurt?

Beyond the personal connection, these questions ask the recipient of the message to consider the potential loss that would be incurred if their cavalier attitude toward safety resulted in them getting injured.

Social psychologist Daniel Kahneman coined the term “loss aversion” to describe the human tendency to strongly prefer avoiding a loss to receiving a gain. In this context, there are times when we could be more effective in persuading someone to behave differently (exhibit safe work habits) by pointing out what they stand to lose by taking a risk, rather than what may be gained by working safely. The kinds of questions like those listed above are intended to have the person reflect on the possibility of a significant personal loss. In other words, we want them to develop a future-looking mindset that influences their current actions.

Conclusion

Would Greg have made a different decision about passing a vehicle on a double line if he thought about the future with his family? We will never know.

One lesson that I remember from my driver’s education class as a teenager sticks with me to this day. My instructor asked each of us to consider the following question when deciding whether to pass another vehicle by crossing the double line on a two-lane road: “Is this choice worth the short term gain in time?”

Perhaps a stronger question to ask ourselves (or others) would be, “Is the potential for suffering and loss worth taking an unnecessary risk?”

References

https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/loaded/201701/time-is-money-not-you-think

Photo credit: DepositPhotos. Image ID:32716307. Standard License.