“I am always doing that which I can not do, in order that I may learn how to do it.”

– Pablo Picasso

As the engineering manager of a large manufacturing facility, Rick had a knack for identifying talent. Whether he was recruiting on campus or interviewing candidates with some experience, Rick had a set of criteria that guided his decision-making. It started with GPA and class rank, but also included other accomplishments such as patent applications, publications, research grant awards, and other recognition. Everyone agreed that Rick attracted the best and brightest professionals to join his staff. Rick recruited for exceptional talent.

As the engineering manager of a large manufacturing facility, Rick had a knack for identifying talent. Whether he was recruiting on campus or interviewing candidates with some experience, Rick had a set of criteria that guided his decision-making. It started with GPA and class rank, but also included other accomplishments such as patent applications, publications, research grant awards, and other recognition. Everyone agreed that Rick attracted the best and brightest professionals to join his staff. Rick recruited for exceptional talent.

At the same facility, Karen provided leadership for a process control group. She would accompany Rick on many of the campus recruiting visits. Karen and Rick pursued their respective candidates from essentially the same pool. However, Karen had a different perspective. She wanted to learn about each candidate’s work and social background. She was keen to learn about how they overcame obstacles, struggled to succeed, and learned from their mistakes. The candidates who received offers to join Karen’s group were often (on paper) “second-tier” talent. Each person had solid grades and had the skills needed for the job, but they were not exceptional. Karen recruited for growth potential.

What happened when these employees joined the company? It is a tale of two divergent philosophies.

In Rick’s organization, you were expected to jump right in and contribute right away. You were judged as either competent or incompetent within the first few months. If you could not deliver on a more complex project, you were relegated to more routine assignments. Rick’s idea of coaching was to highlight any errors, which created a fear of failure. Rick frequently reminded others that he was “the smartest guy in the room” in group meetings. Engineers either left the company or actively looked for other opportunities in another department. Turnover in the engineering group was typically 30% within the first two years, with the majority of these employees seeking other employment.

Meanwhile, Karen fostered an environment of personal growth and potential. While she certainly wanted good people on her staff, Karen saw basic talent as an entry ticket. She set up a formal process where each protégé was assigned a mentor. She held weekly meetings where the team was encouraged to share any learning – especially those that came with making mistakes. Individual performance improvements were noted and recognized. Karen also asked for feedback on how she could be more effective as their manager. Turnover in the process control group was also about 30%. But almost all of her employees were promoted to positions of increased responsibility within the same company. Karen’s group became the de-facto internal talent pool for many supervisory positions.

The difference between these two approaches are stark. They are characteristic of two philosophies, described by Carol Dweck as the fixed mindset and the growth mindset, respectively. In her book, Dweck provides an in-depth look into each of these mindsets. She contrasts the outcomes of each mindset when it is adopted by parents, teachers, coaches, and leaders. A comparison of the two is given below.

Fixed Mindset |

Growth Mindset |

| Your intelligence is something very basic about you that you cannot change very much | No matter how much intelligence you have, you can always change it quite a bit |

| You can learn new things, but you really can’t change how intelligent you are | You can always substantially change how intelligent you are |

| You are a certain kind of person and there is not much that can be done to change that | No matter what kind of person you are, you can always change substantially |

| You can do things differently, but the important parts of who you are can’t be changed | You can always change the basic things about the person you are |

In the following clip from a TED talk, Eduardo Briceno provides an overview of Dweck’s research. Note that both mindsets are observable in children, as well as adults.

Others have described an attribute that is related to the growth mindset. It is claimed to be a better predictor of success than IQ. The term “grit” was popularized by Angela Duckworth, a psychology professor at the University of Pennsylvania. She defined it as the “quality of being able to sustain your passions and work really hard at them, over really disappointingly long periods of time.” Duckworth explained that people with grit are those who can overcome stress. In addition, they use failure as a means to achieve their goals.

Because Rick has a fixed mindset, he seeks out those whom he believes can be successful immediately and require minimal coaching. Ironically, a disproportionate number of the employees who join Rick’s organization are likely to also have a fixed mindset. This is a tragic combination. The manager expects performance from his employee with minimum personal investment, while the new employee expects to excel and be quickly recognized or rewarded – because they have always been the most talented among their peers. Ultimately, both are disappointed or disillusioned.

Most of the employees that Karen recruits demonstrate a growth mindset (and are also more likely to have “grit”). Karen believes that each employee has the potential to be a high performer. But she recognizes that this potential has to be nurtured. Further, there are plenty of opportunities for learning to occur when mistakes are made. In her view, the key is to provide encouragement for each protégé. Karen role models the growth mindset through her actions. She seeks and accepts critical feedback from her employees for the purpose of personal growth. It is not surprising that most of her employees achieve a new level of performance and are recruited internally.

The mindset of those who are in leadership positions is a principal driver in how they set expectations. As discussed in a previous post, people often perform to the level of expectation that is placed upon them. Fixed mindset leaders expect talented people to perform well and those with less talent to struggle. Further, they believe that there is not much you can do to change this outcome.

Fortunately, the growth mindset can be taught to managers. Heslin and his colleagues proved this by designing and conducting a workshop with this goal.

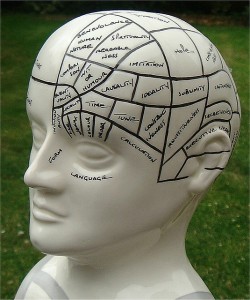

The workshop starts by helping people understand how the brain is dynamic. It shows how the brain changes with learning and claims that just about anyone can develop new abilities, regardless of their age, with coaching and practice. The workshop also includes exercises where the participants:

- learn why it is important to understand that people can develop their abilities

- think of personal examples of when they started with low ability, but now perform at a higher level

- write to a protégé who is struggling with some encouragement

- reflect on a time when they saw someone learn to do something that they never thought they could do.

Interestingly, the participating managers were much more willing to coach a poor performer and were more likely to provide coaching suggestions. These traits persisted many weeks after the workshop concluded.

There are several implications of this work. The authors conclude that a growth-mindset environment can be created that will yield huge dividends in terms of leveraging the full potential of all employees, regardless of their innate skills. In order to foster such an environment, leaders need to –

- believe that all skills can be learned

- communicate that the organization values learning and perseverance (not just ready-made genius or talent)

- provide feedback that promotes future learning

- insist that managers are available as key resources for learning, not just to direct work.

Conclusions

Reflect on your own beliefs in this context.

Do you believe that you can learn new things, but you really can’t change how intelligent you are? Do you believe that you are a certain kind of person and there is not much you can do to change that? Do you value existing talent over learning? If so, you have a fixed mindset.

The first step toward realizing your full potential is an honest self-assessment. If you have a fixed mindset, develop a plan to move toward a growth mindset by deploying some of the strategies proposed by Dweck, Heslin, and others.

If you are in a leadership role, take what you learn and create an environment that nourishes a growth mindset within your organization. The results will surpass your expectations.

References

Keen to Help? Managers’ IPT and Their Subsequent Employee Coaching. Heslin, VandeWalle, and Latham. Personnel Psychology 59 (2006) 871-902.

Mindset. The New Psychology of Success. Carol S. Dweck. Ballantine Books. New York. 2008. ISBN 978-0-345-47232-8.

http://fortune.com/2014/06/19/career-wise-is-it-better-to-be-smart-or-hardworking/

Photo credit: https://flic.kr/p/9MxAz (Luke G.)