It takes at least two people to have a conversation. For a conversation to be effective, each person needs to alternatively talk and listen. Unfortunately, some leaders are prone to lecturing, with very little listening. This ineffective communication style isn’t isolated to senior leaders who ascribe to the command-and-control approach to management. It can be seen at all levels of organizations.

It takes at least two people to have a conversation. For a conversation to be effective, each person needs to alternatively talk and listen. Unfortunately, some leaders are prone to lecturing, with very little listening. This ineffective communication style isn’t isolated to senior leaders who ascribe to the command-and-control approach to management. It can be seen at all levels of organizations.

The prevalent communication style of managers and supervisors is a barometer of the safety culture. Occasional, one-way safety conversations are telltale signs of a culture of compliance. Frequent, interactive safety conversations are indicative of a culture of commitment.

As indicated in a previous post, the motive for having a conversation significantly influences the safety culture. To recap:

- If the reason you have any safety conversation is to exert control, the approach will be to criticize and seek compliance through correction.

- If the reason you have any safety conversation is because you care, the approach will be to coach and seek commitment through collaboration.

One communication model1 suggests that an effective organizational conversation has four attributes: intimacy (building trust and listening), interactivity (promoting discussion), inclusion (collaborating on solutions), and intentionality (sharing a common purpose).

In this article, I introduce a guide for an effective safety conversation – one that starts with caring. This guide incorporates the four attributes of an effective conversation. It also stimulates a conversation that enables coaching and collaboration.

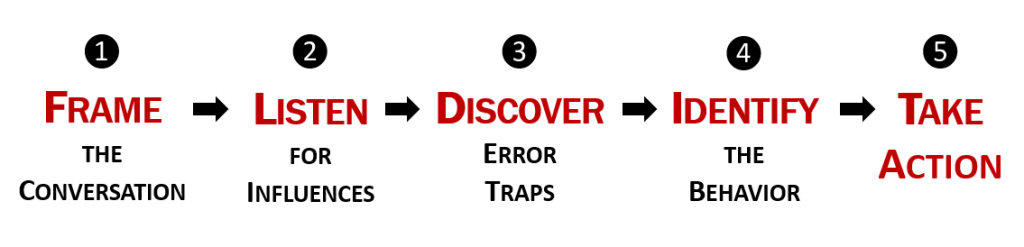

Five-Step Guide for a Safety ConversationTM

This framework can be applied whether the conversation is reactive (after an incident) or proactive (identifying influences on risk or conditions that may cause errors).

When you initiate a safety conversation with an employee, the first few moments set the stage for what follows. Your intent will be clear to the listener by your body language, your words, and your tone.

When you initiate a safety conversation with an employee, the first few moments set the stage for what follows. Your intent will be clear to the listener by your body language, your words, and your tone.

If your words indicate that you need control, then you are not having a conversation. Instead, you are signaling your intent to deliver a message.

- “We’ve got a problem”

- “You know the safety rules”

- “I expect you to follow them”

In this case, the employee immediately feels defensive. He is likely to share only the minimum amount of information.

On the other hand, if you frame the conversation with care and concern, the discussion is much more likely to be interactive. You do this by asking questions in a non-threatening way.

- “Can you help me?”

- “What is the major risk?”

- “What mistakes could be made?”

You are making it clear that you need their help. The employee is being encouraged to participate in a genuine dialogue.

The only way you can learn about hidden process or organization issues is to ask the right questions in the right way – and then listen. Most of us believe that we are good listeners. But research shows that we seldom hear what people are saying in the way it was intended to be heard. Active listening is hard work!

The only way you can learn about hidden process or organization issues is to ask the right questions in the right way – and then listen. Most of us believe that we are good listeners. But research shows that we seldom hear what people are saying in the way it was intended to be heard. Active listening is hard work!

Of course, if your original motive is control, you are not listening – you are telling. You are stating your case either for what was done incorrectly or what rule or policy was not followed.

By contrast, an effective safety conversation includes listening for the responses to all questions. You are seeking to learn about any potential influences on risk. People don’t take risks without a reason. As someone once said,

“People do what they do because it made sense to them at the time that they did it.”

Your challenge is to find out why it made sense to the employee to take an unnecessary risk. Often times, the reason is that they were influenced in some way.

The four-part risk model2 is a good outline for identifying the major influences on risk: perceptions, habits, obstacles, and barriers. If the conversation takes place after an incident or near miss, listen for indications that one of these factors was in play if an employee took an unnecessary risk. In a proactive conversation, inquire how someone might be influenced to take a risk when performing a specific task.

For a supervisor who wants to maintain or exert control, rules and policies are edicts. If an incident occurs, the first thing he wants to know is the procedure, rule, or policy that was not followed. If someone gets hurt, it almost always means that one of these was violated. In a compliance world, many people believe that if you just follow the rules, you won’t be seriously injured.

For a supervisor who wants to maintain or exert control, rules and policies are edicts. If an incident occurs, the first thing he wants to know is the procedure, rule, or policy that was not followed. If someone gets hurt, it almost always means that one of these was violated. In a compliance world, many people believe that if you just follow the rules, you won’t be seriously injured.

If caring drives the conversation, a supervisor knows that another critical part of listening is to discover potential error traps. These are conditions or circumstances that make it more likely to make a mistake3. A few examples are listed below:

- Time Pressure

- Distraction

- Vague Guidance

- Multiple Tasks

- Complacency

- Peer Pressure

These error traps may emerge as part of the conversation. Or a supervisor may find additional ones when he takes a holistic view of the situation. Either way, acknowledging these error-prone conditions is the first step in finding ways to mitigate their effects.

Dr. James Reason4 first described a Just Culture in the 1990’s. Others, including David Marx5, later clarified this concept. One definition is “a culture where failure/error is addressed in a manner that promotes learning and improvement while satisfying the need for accountability.” Using this model, Marx listed three possible behaviors that might contribute to an undesirable outcome:

Dr. James Reason4 first described a Just Culture in the 1990’s. Others, including David Marx5, later clarified this concept. One definition is “a culture where failure/error is addressed in a manner that promotes learning and improvement while satisfying the need for accountability.” Using this model, Marx listed three possible behaviors that might contribute to an undesirable outcome:

- Human Error

- At-risk Behavior

- Recklessness

A supervisor whose motive is control often assumes that the primary reason for a safety incident is (a) someone made a mistake or (b) someone made a poor choice. With this mindset, it is not a surprise when the supervisor attempts to “correct” the behavior through some kind of admonishment.

If a human error is involved, the employee may hear something like, “Pay more attention” or, “Keep your mind on the job.”

If an employee is deemed to have made a poor choice, he may be challenged to “Think before you act next time” or even, “Just don’t do stupid things!”

In contrast, a supervisor who believes in a Just Culture realizes that more than 90% of the time people are ‘set up’ to make a mistake (by error traps) or are influenced to take a risk (by a perception, habit, obstacle, or barrier). This supervisor realizes that truly reckless behavior rarely happens.

His focus in a safety conversation is to actively listen for influences and error traps. The employee’s behavior is identified as reckless only when there is a choice to consciously disregard a substantial and unjustifiable risk.

Reckless behaviors exist in the industrial world, but they happen only occasionally.

A supervisor who expects to maintain control takes actions which are directed toward compliance. These are typically some form of re-training, warning, counseling, or discipline.

A supervisor who expects to maintain control takes actions which are directed toward compliance. These are typically some form of re-training, warning, counseling, or discipline.

In a culture of compliance, supervisors assume that people should perform work using standard procedures and abide by the safety rules. If they do not, then they need to be held accountable.

It is a mistake to simply warn, counsel, or discipline someone for not using a procedure or following a safety rule without understanding the reason for this decision. There could be hidden organization or process issues that influenced the employee. Sydney Dekker identified numerous reasons for what he termed procedural drift (a mismatch between standard procedures or rules and actual practice that increases over time). For example:

- Rules or procedures may be over-designed and do not match up with the way work is really done.

- There may be conflicting priorities which make it confusing about which procedure is most important.

- Procedures may be vague, poorly written, or outdated.

In a culture of commitment, a safety conversation concludes on a very different note. Because the conversation proceeds in a spirit of learning and co-discovery, the actions are built on collaboration.

When a mistake is identified, the supervisor seeks to understand and mitigate any error traps. In some cases, this could include a collaboration on mistake proofing solutions. These are simple process design changes that make it easy to do the right thing and difficult to do the wrong thing.

If an employee drifts into an at-risk behavior, the type of influences on risk determine the best course of action. Coaching is often effective for perceptions or habits. Like addressing error traps, a collaborative effort is a common approach to removing obstacles or barriers.

Counseling or discipline is warranted for truly reckless behavior.

A Critical Influence Strategy

Using this five-step guide, anyone can conduct an effective safety conversation. It is designed to be used when your primary objective is to promote learning and improvement.

This guide is centered on the “Why” of caring. When you start with this motive, the conversation that follows is more open. The real pay-off in having a candid dialogue is in discovering the hidden weaknesses in the process and in the organization. Making these visible is essential. It sets the stage for collaboration to improve the work processes and to eliminate sources of failures or errors.

Supervisors and managers need to be skilled in facilitating effective safety conversations. Having a daily proactive safety dialogue like the one outlined here is a cornerstone in building a culture of commitment. This conversation should be an integral part of your safety strategy.

What will you learn (and improve) as a result of your next safety conversation?

Click here for instructions on how to download a free mobile app that follows this five-step process: Safety Conversation Guide

References

1Leadership is a Conversation. Boris Groysberg and Michael Slind. Harvard Business Review. June, 2012.

2Understanding influences on risks: a four-part model. Terry Mathis and Shawn Galloway. EHS Today. February, 2010.

3Practicing Perfection Institute, Inc. Error Elimination Tools. 2012.

4Managing the Risks of Organizational Accidents. Reason, James. Hampshire, England: Ashgate Publishing Limited. 1997.

5Whack-a-Mole. The Price We Pay For Expecting Perfection, by David Marx. Your Side Studios. 2009.