It was noisy in the meeting room as the construction workers assembled early one morning. The concrete floor and cinder block walls created an echo chamber for the men’s voices and the squeaking of metal chairs being pushed into place. Spartan furniture and a dusty, bare floor were tell-tale signs that this room was used occasionally for crew meetings, but not much else. Some folding tables on one side of the room strained under the weight of 3-ring binders and manuals stacked half-way to the ceiling. Another table in the back held a large coffee urn and numerous boxes of doughnuts, most of which had already been claimed.

It was noisy in the meeting room as the construction workers assembled early one morning. The concrete floor and cinder block walls created an echo chamber for the men’s voices and the squeaking of metal chairs being pushed into place. Spartan furniture and a dusty, bare floor were tell-tale signs that this room was used occasionally for crew meetings, but not much else. Some folding tables on one side of the room strained under the weight of 3-ring binders and manuals stacked half-way to the ceiling. Another table in the back held a large coffee urn and numerous boxes of doughnuts, most of which had already been claimed.

While Russ went to the front of the room to get the projector running, I settled into a metal chair beside the doughnut table, fighting the urge to grab one of the few remaining sugary treats. Russ was the internal trainer. He was scheduled to talk to the group for the first hour.

The class about safety culture and leadership had been requested by the contractor’s leadership team. The company recently had some serious injuries and near misses. They were anxious to see what could be done to prevent another event.

The managers were perplexed why some of their guys were taking risks, even though they had implored them to “be careful.” Even more disturbing, it seemed as though someone was making a mistake on the job almost every week. While all of these were small errors, the senior managers knew that any one of these mistakes could cause significant property damage or result in another injury under different circumstances.

As Russ went through the introductory slides and started the first class exercise, a burly man dressed in blue jeans and a shirt that appeared to be one size too small abruptly emerged from an office which adjoined the conference room. The name plate and title above the door indicated that Ed was a supervisor. Ed yanked his office door closed behind him, causing a loud thud when it met the door jamb. I heard him mutter a couple of expletives as he walked briskly by my chair and walked heavily down the stairs on the far side of the room.

Much to my surprise, no one sitting in the metal chairs even turned around to see what all the commotion was about. They acted as if this was a normal occurrence. In the front of the room, Russ cleared his throat and clicked to the next slide in the presentation.

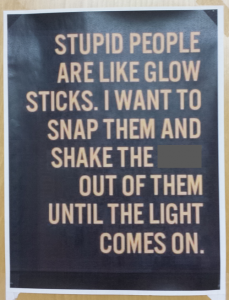

When I turned back to Ed’s office, I spotted a large poster taped to the outside of his closed door. (The obvious missing word has been redacted).

“Hmmm,” I thought, “I wonder if this poster reflects his philosophy as a supervisor.”

I decided to learn more about Ed before jumping to any conclusions.

At the first break, I casually asked several of the guys about Ed. After a bit of hesitation, a few of them opened up.

One fellow took a long drag on his cigarette, looked around to see if anyone was within earshot, and told me in a low voice, “The way you deal with Ed is to keep your head down and don’t ask questions. If you’re lucky, you can get to your truck and be on the road before he corners you about something that you did wrong.” The guy beside him shuffled his feet in the dirt and nodded in silent agreement.

At the lunch break, I carefully quizzed a few other guys. One response in particular seemed to sum up Ed’s approach to people. A tall, lanky man with a full beard and sleeve tattoos offered that, “For Ed, there are two kinds of people in the world: Those who can, and those who never will.”

Near the end of the class, I decided to talk with Ed. After all, many of the men in this class were guys on his crew. I needed to hear directly from him. (Ed didn’t participate in the class. He explained to Russ that he was too busy “putting out fires”).

After engaging in small talk, I asked Ed which guys he thought were his best workers. “That’s simple,” he said. “I need somebody who shows up on time, takes direction, and doesn’t screw up too often. Anything else is a bonus.”

Although I expected a response something like the one he gave, I was still taken aback. So I pressed him a bit and asked if he was able to coach anyone who was struggling a little when they were new on the job. “Heck, no! Look, we don’t have time to babysit these guys. Either they get it, or they don’t. After all, you can’t coach stupid”

I had my answer. The poster was not only crude humor. It also reflected the philosophy of the man who taped it to his door!

Ed’s phone came to life and vibrated on his desk. He picked it up, looked at me, and motioned me toward the door with his free hand. The conversation ended.

I left his office with a sour feeling in my gut.

Not every person in this organization shared Ed’s misguided approach. I met some other supervisors who seemed to be even-keeled in how they led their crews. However, it was clear that this supervisory group as a whole could benefit from coaching skills.

Ed is an extreme case of someone who has a fixed mindset. As referenced in a previous blog post, psychologist Carol Dweck first explained the differences between a fixed mindset and a growth mindset. In Ed’s world, people either had the “right stuff” or not. He dismissed the belief that you can coach people to a higher level of performance, which is a hallmark of someone with a growth mindset.

Supervisors or managers with a fixed mindset severely limit the progress of the organization. Employees whom they supervise tend to be disengaged. Turnover is high. Trust is minimal. Success is measured in absolutes. And perhaps most importantly, learning and improvement are crushed.

This combination of outcomes from a fixed mindset approach makes it impossible to foster a Just Culture –defined as the middle ground between a highly punitive system and a culture where no one is accountable. A Just Culture is the foundation for achieving an environment centered on commitment.

Is it any wonder that this company struggled with their safety performance?

When I talked to one of the senior managers, I learned more about Ed. I was told that his promotion as a supervisor over 10 years ago was largely based on his work ethic and being able to get the job done. Any training sessions for supervisors were almost exclusively directed toward improving their technical skills. Neither Ed nor any of his peers were provided with any coaching skill development.

What should be done? One manager confided that Ed was considered a true subject matter expert. Many of the other supervisors came to Ed for advice – not about people (thankfully), but how to solve a particularly thorny or difficult construction problem.

I recommended that Ed be given the opportunity to learn how to coach others. This could not be limited to a few hours of advice. It needed to include someone to mentor Ed in applying and practicing coaching skills. He would need immediate and candid feedback.

Further, I advised that if Ed did not demonstrate a willingness to learn and implement basic coaching as part of the way he supervised others, then the manager would have a choice. Either he could allow Ed to stay in his current role and allow him to continue to poison the organization. Or he could make the hard decision to find another position where they can benefit from Ed’s expertise – a role that had no direct supervisory responsibility.

We don’t want to just give up on people like Ed. If we did, then we could rightly be accused of harboring the same fixed mindset that we want to change! However, we should not tolerate behaviors associated with an extreme fixed mindset. Anyone in a significant influencing role should know how to use basic coaching skills. Or they need to find another line of work.

It’s the only way for an organization to grow and provide a work environment that is safe – both physically and emotionally.

References

Monique Valcouris. HBR.org. April 2016. https://hbr.org/2016/04/people-wont-grow-if-you-think-they-cant-change