As a leader, do you spend more time asking or telling?

As a leader, do you spend more time asking or telling?

In the United States, we have a culture of “Do” and “Tell”. We value task accomplishment more than relationship building. It is a cultural bias that many of us have. Many people in a supervisory or managerial role spend most of their time telling others what we think they need to know to get a job done, rather than asking for their input.

Status in most workplaces is gained by task accomplishment. We are recognized and rewarded for getting things done. Indeed, one of the most significant factors that determines whether someone is promoted or given more responsibility is the ability to complete work assignments.

In some cases, a mostly “tell” approach is all that is required to get a task accomplished. Some examples include situations where the work is straightforward or where the employee is inexperienced. These interactions are characterized by almost exclusively one-way communication. While we can get work done using a telling approach, it does very little to build relationships.

There is a significant amount of interdependence in today’s workplace. We need effective communications and good relationships to be successful in completing complex tasks. To build these relationships, we need a different technique other than simply “telling.”

In this article, we compare the strategy of telling with one that is centered on a specific kind of asking known as humble inquiry. We will learn that this attitude is critical for improving communications, developing relationships, and building trust.

The notion of humble inquiry was originally developed and explained by Edgar Schein. He defines humble inquiry as:

“…asking questions to which you do not already know the answer; building a relationship based on curiosity and interest in the other person.”

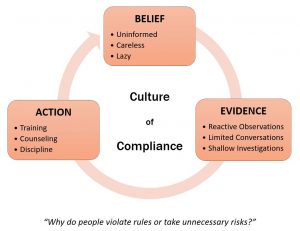

The strategy of asking by using humble inquiry is especially critical for facilitating an effective safety conversation. Many safety conversations that are initiated by people in authority are missing this key attribute. Unless you are willing to ask questions from a basis of genuine care for the employee, you will not build trust. Continue Reading