Victor has over 20 years experience in the warehouse. You have a few years of experience and were just hired a few weeks ago. Today, you are working as a team, unloading pallets of packaged materials that were delivered from the dock. As both of you approach the first pallet, Victor takes a position directly in front of the strapping that is straining under tension. You see that this puts him in the line of fire. Instinctively, you take a step back when Victor pulls a pair of snips from his pocket to cut the strapping…

Victor has over 20 years experience in the warehouse. You have a few years of experience and were just hired a few weeks ago. Today, you are working as a team, unloading pallets of packaged materials that were delivered from the dock. As both of you approach the first pallet, Victor takes a position directly in front of the strapping that is straining under tension. You see that this puts him in the line of fire. Instinctively, you take a step back when Victor pulls a pair of snips from his pocket to cut the strapping…

Do you speak up? Do you stop him? Are you sure?

Perhaps you would say something. But a surprising number of people in this situation would stay silent. Their thought process would be something like, “Surely he must know how to perform this task safely. He’s done it thousands of times. I’m the rookie here. Who am I to question his experience and job knowledge?”

Peer pressure is a powerful social influence. Most of us are fearful of being considered an outcast if we are the dissenter, especially if we have less informal authority than other people in our natural work group.

You may think of peer pressure as overt statements from co-workers. “Look, this is the way things are done around here.” But this is not always the case. In the scenario above, Victor did not have to remind you about his seniority and experience. It was implied and understood.

Propensity for Silence

Over 1500 employees from a dozen locations have taken my eight-question safety culture survey. One question from this survey is designed to gauge an employee’s willingness to speak up:

How comfortable are you in stopping and talking to a co-worker if you see them taking an unnecessary risk, even if they are more senior than you?

People who answered this survey question and selected the lowest rating (on a scale from 1 to 5) described their response as “Definitely Uncomfortable. It’s not my job to question someone else’s work, especially if they are very experienced.”

Those who chose the highest rating on the scale assessed themselves as being “Very Comfortable. I have a responsibility to speak up to anyone – regardless of their authority. I would expect them to do the same for me.”

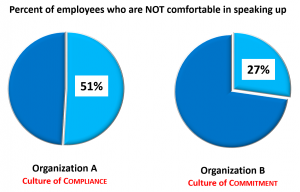

The percent of responses on the lower end of the scale (ratings of 1, 2, or 3) were combined to attain the overall percent of employees who were not comfortable (to some extent) in speaking up.

A comparison of responses to this question from two organizations is given below. Each organization is at a very different place along the Safety Leadership ContinuumTM (explained in an earlier post and in this short video).

- Organization A is characterized by a culture of compliance. They have a poor safety performance relative to their industry peers. Half of the employees who completed the survey reported that they were not comfortable in speaking up.

- Organization B has a strong culture of commitment. They have an excellent safety record. However, even in this organization more than 1 in 4 persons were not comfortable in speaking up.

These findings confirm that a significant number of employees hesitate to speak up when they see someone taking an unnecessary risk. If even one individual doesn’t speak up when they see someone taking a risk, it could be the difference in whether they or their co-worker are injured. Staying silent is a workplace behavior that can have tragic consequences.

Before we can identify methods to improve the likelihood that someone will speak up, we need to understand some potential factors that contribute to this behavior. A study of global plane crashes revealed a major reason why people remain silent, even when it seems obvious that they should say something.

A Cultural Dimension

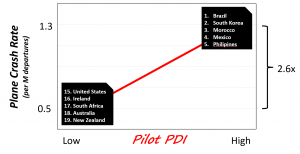

An analysis of commercial airline incidents showed that plane crash rates (per million departures) are significantly different when compared across countries. However, after ruling out variations in equipment, technology, training, maintenance practices, etc., researchers remained puzzled about this discrepancy in safety performance. Could there be a cultural component that would explain these differences?

Geert Hofstede, a Dutch psychologist, developed the Power Distance Index (PDI) as part of his work to understand and measure certain cultural attributes. Power Distance is concerned with attitudes toward hierarchy – specifically with how much a particular culture values and respects authority. The greater the PDI, the less likely an employee will disagree with their superior (or someone who has more power).

To determine the PDI, Hofstede conducted cultural surveys in nearly two dozen countries. He asked questions such as:

- How frequently, in your experience, does the following problem occur: employees being afraid to express disagreement with their managers or superiors?

- To what extent do the less powerful members of the organization accept and expect that power is distributed unequally?

- How much are older people respected or feared?

- Are power holders entitled to special privileges?

When Hofstede plotted the PDI associated with the pilot’s native country against their respective plane crash rates, he determined there was an association between these two factors. The pilots from countries with the highest Power Distance Index were over 2.5 times more likely to crash than the pilots from countries with the lowest PDI.

Moreover, plane crashes are much more likely to happen when the captain is in the “flying seat”, even though they share the flying time about equally. Why? The evidence suggests that the junior officer in the cockpit is reluctant to question the captain (who has more authority) when he or she sees something that may be an unsafe decision.

The higher the PDI of the flight crew’s native country, the less likely the co-pilot will be to speak up when something does not seem right. This reticence is believed to be a significant contributor to the higher crash rate.

Let’s consider these implications in the context of a non-aviation workplace.

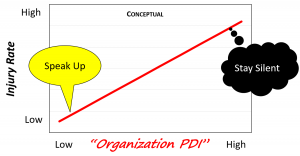

Just as the cultural norms among nations are not the same, the norms among organizations can be extremely different.

Imagine if we measured the PDI of those companies who set the standard for safety, as well as the PDI of organizations with poor safety performance. My hypothesis: We would find a relationship between organization PDI and employee injury rate (analogous to the pilot PDI vs crash rate study described earlier).

Based on the results of the survey question presented earlier, there is empirical evidence that this relationship exists. Certainly, there are many other factors that contribute to a culture of commitment and a safe work environment. But if a significant proportion of employees stay silent, it is a symptom of an organization that manages safety mostly through compliance. In a work environment where blame and/or fear are common, there is little doubt that silence will prevail.

Escalating Concern

The airline industry made changes to address the identified cultural communication gap. Crew resource management training is now standard in the industry. It is designed to teach junior crew members how to communicate clearly and assertively.

There is a standard procedure for co-pilots to challenge the pilot if he/she thinks something has gone wrong or a poor decision is being made. It is a set of escalating statements:

- “Captain, I’m concerned about…”

- “Captain, I’m uncomfortable with…”

- “Captain, I believe the situation is UNSAFE.”

(If the captain does not respond, the first officer is required to take over the aircraft).

Has this training worked?

South Korean people have a high Power Distance Index – and historically pilots from this country suffered a high plane crash rate. Since these changes in crew resource management training, South Korean commercial aviation crash rates are now in line with those countries with a low PDI (see the earlier graphic). Note that South Korean culture still has a high PDI. But the pilots have been trained to behave quite differently once they enter the cockpit. They are now much more likely to speak up and question the captain if they see or hear something that could jeopardize the safety of the flight.

We could take a page from the crew resource training manual and apply it to an industrial setting. Why not give employees the skills to speak up, using a standard protocol?

For example, the procedure for anyone to challenge a co-worker when he/she thinks that person is taking an unnecessary risk could be the following:

- “_________, I’m concerned about…”

- “__________, I’m uncomfortable with…”

- “__________, I believe the situation is unsafe.”

If __________does not respond, the task is stopped. Work does not proceed until someone else is consulted.

The Power of One

Just because we educate employees on how to escalate a concern, it does not mean they will have the courage to do so. We need to appreciate the powerful force of social influence. In this video, David Maxfield and Joseph Grenny explain the power of having just one person in a group speak up in dissent. They suggest that we express our disagreement using polite doubt.

Leading Change

How can we get employees to speak up when they see risky behavior? Here are some actions we can take to reduce an organization’s Power Distance Index:

- Set a clear expectation that everyone (even the most junior employee) is empowered to speak up whenever something doesn’t seem right.

- Look for opportunities to positively reinforce this behavior when it is observed. Communicate the importance of doing this by citing examples or telling stories of others who spoke up – thus preventing a decision or action that otherwise would have resulted in a negative outcome.

- Be a role model for how to receive feedback. Publicly praise anyone who voices a concern. This is especially critical if this person questions a decision or expresses an opinion that is counter to the majority view.

- Provide training on how to raise and quickly escalate a concern, à la the crew resource training method used by the airline industry. Standardize the way employees can respectively disagree or pose a question when there is a hierarchy that may inhibit the behavior to speak up. Teach the concept of disagreeing through polite doubt.

- Enlist opinion leaders in the effort to make “speaking up” an accepted and expected behavior. These are people who are “respected and connected” in the organization. However, they may not have any formal authority. If you can get this group to speak up, it sends a signal to others that it is an acceptable norm.

- Facilitate a discussion about this topic in natural work groups. Have them commit to one another that (a) they will speak up and (b) they will listen when anyone questions a decision or believes that situation is not safe.

We cannot achieve a zero event work place unless we create an environment where employees are watching out for one another. But simply watching is not enough. We need everyone to be comfortable enough to take action and speak up when they see anyone taking an unnecessary risk – every time!

References

Geert Hofstede. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations. Sage Publications. Thousand Oaks, CA. 2001

Robert L. Helmreich and Ashleigh Merritt. “Culture in the Cockpit: Do Hofstede’s Dimensions Replicate?” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 31, no.3 (May 2000): 283-301.

“Culture May Play Role In Flight Safety — Boeing Study Finds Higher Aviation Accident Rates Among Nations Where Individualism Not The Norm”. Don Phillips. The Washington Post. August 22, 1994.

Ute Fischer and Judith Orasanu. “Cultural Diversity and Crew Communication.” Astronautical Congress. Amsterdam. October 1999.

One Simple Skill to Overcome Peer Pressure. https://youtu.be/1-U6QTRTZSc

http://ehstoday.com/safety-leadership/control-or-caring-what-your-motive-safety-conversation