“Raise your hand if you believe that you are pretty good at multitasking”.

“Raise your hand if you believe that you are pretty good at multitasking”.

When I present this challenge to a group, typically about half of the people in the room respond by lifting their arms in the air. Then we have a discussion about what multitasking is and why NO ONE has this “skill.” We also use a simple exercise that demonstrates what is really happening with our brains when we attempt to take on two cognitive tasks at the same time (more about this exercise later).

Dave Crenshaw has blogged and written extensively about multitasking. His premise is that this phenomenon simply does not exist. In fact, he calls it a myth.

If you are one of those persons who raised your hand, perhaps you are thinking, “I’ve been juggling many things for a long time and I think I’ve been pretty successful in doing so. What do you mean there is no such thing as multitasking?”

Crenshaw prefaces his argument by providing a few definitions:

When I speak of multitasking as most people understand it, I am not referring to doing something completely mindless and mundane in the background such as exercising while listening to (a) CD, eating dinner and watching a show, or having the copy machine operate in the background while you answer emails. For clarity’s sake, I call this “background tasking”.

When most people refer to multitasking they mean simultaneously performing two or more things that require mental effort and attention. Examples would include saying we’re spending time with family while were researching stocks online, attempting to listen to a CD and answering email at the same time, or pretending to listen to an employee while we are crunching the numbers. What most people refer to as multitasking, I refer to as “switchtasking.”

Many studies in the field of neuroscience have confirmed that we are indeed incapable of multitasking. When it comes to the brain’s ability to pay attention, the brain focuses on concepts sequentially and not on two things at once. In fact, the brain must disengage from one activity in order to engage in another. And it takes several tenths of a second for the brain to make this switch. As John Medina, author of Brain Rules says: “To put it bluntly, research shows that we can’t multitask. We are biologically incapable of processing attention-rich inputs simultaneously.”

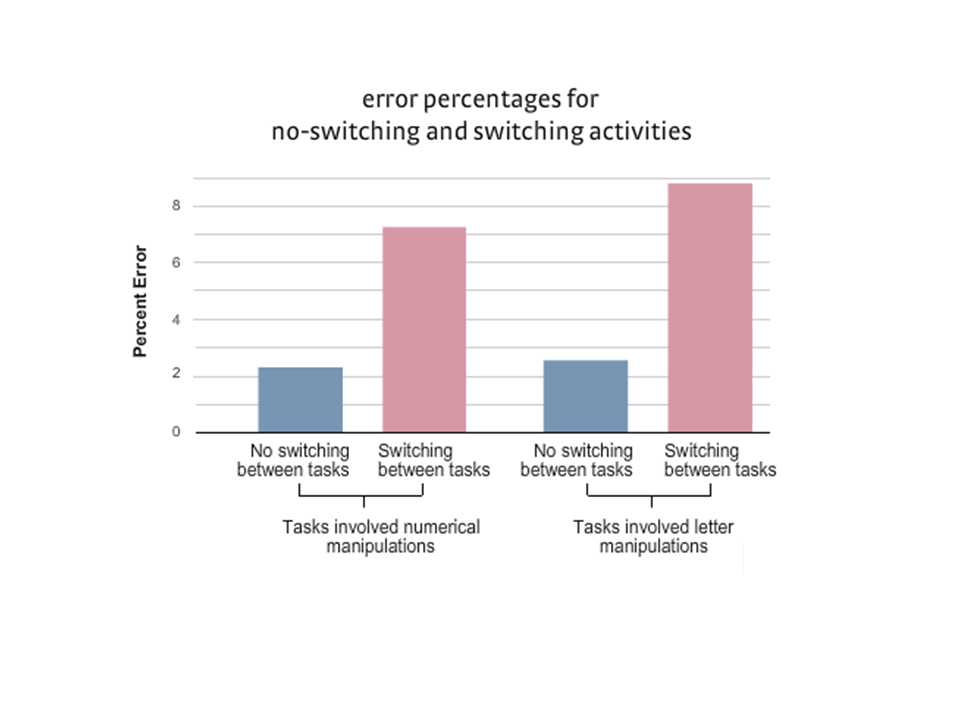

Medina also cites studies which confirm the cost of all this switching back and forth among various tasks. The chart below illustrates that our error rate is 3 to 4 times higher when we are required to switch between tasks!

These data support the concept of distractions and multi-tasking being “traps” – when mistakes are much more likely to happen. The Practicing Perfection Institute has developed an Error Elimination Tools Handbook, which is especially helpful when you know you are in one of these situations.

Want even more “sobering” statistics? Studies have shown that using a cell phone while driving is akin to drunk driving. Compared with people who only drove a car, those who talked on a cell phone while driving:

- Had 4x more collisions.

- Were 19% slower in resuming their normal speed after braking.

- Had 25% more variation in following distance as the cellphone driver’s attention state shifted between talking and driving.

If you would like to test your multitasking performance, download and complete the simple exercise below, which was originally developed by Crenshaw.

So what can we do about all these distractions that reduce our productivity, heighten our stress, increase our probability of mistakes – and at times increase the risk for accidents or injuries? In short, we have to make a conscious effort to manage and control them. Here are a few suggestions:

- It can start with simple behavioral changes like turning off your cell phone, email, or instant messaging notifications. Check and process any messages or emails in batches. Some have advocated spending only 20 minutes at a time working on electronic messaging – then taking another block of an hour or so before checking for any new messages. You will end up being much more productive because you will be focusing on a single task or series of tasks in sequence, rather than in parallel.

- To the extent that you can schedule things, do this as well. Too often we just let things arise throughout the day and deal with them when they happen. You cannot do this with everything, of course. But it is another way to lessen the number of potential distractions.

- Here is perhaps the most important behavioral change. Don’t text/talk and drive! Many people will need a strong trigger to stop this habit. If you are tempted by the phone that may ping or ring while you are driving, put it in “airplane mode” before you get into the car. There are mobile phone apps which do not allow you to answer or receive calls if the GPS signal detects that the vehicle is moving.

- In the workplace, we should think about the potential for mistakes when people are multitasking or distracted. In an office, it could result in costly errors or rework. In a manufacturing venue, it could be a precursor to defects, poor workmanship, or an accident. As a manager or supervisor, watch out for these traps and consider ways to re-design the work, the schedule, or the environment to minimize the likelihood that multitasking is required to get the job done.

The next time you hear someone claim that they are a “good at multitasking,” point out that they are really switchtasking – a behavior with many risks and a false sense of reward!

References

http://blogs.hbr.org/2014/08/if-youre-always-working-youre-never-working-well/

www.brainrules.net

Strayer, DL, Drews, FA & Crouch, DJ (2006). Fatal distraction? A comparison of the cellphone driver and the drunk driver. Human Factors 48(2): 381 – 391

Photo credit: https://flic.kr/p/8E3DBx. Robert Mehlan.