Victor has over 20 years experience in the warehouse. You have a few years of experience and were just hired a few weeks ago. Today, you are working as a team, unloading pallets of packaged materials that were delivered from the dock. As both of you approach the first pallet, Victor takes a position directly in front of the strapping that is straining under tension. You see that this puts him in the line of fire. Instinctively, you take a step back when Victor pulls a pair of snips from his pocket to cut the strapping…

Victor has over 20 years experience in the warehouse. You have a few years of experience and were just hired a few weeks ago. Today, you are working as a team, unloading pallets of packaged materials that were delivered from the dock. As both of you approach the first pallet, Victor takes a position directly in front of the strapping that is straining under tension. You see that this puts him in the line of fire. Instinctively, you take a step back when Victor pulls a pair of snips from his pocket to cut the strapping…

Do you speak up? Do you stop him? Are you sure?

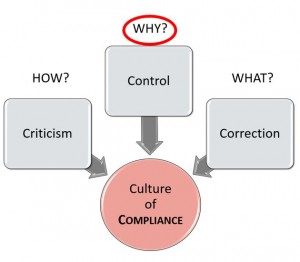

Perhaps you would say something. But a surprising number of people in this situation would stay silent. Their thought process would be something like, “Surely he must know how to perform this task safely. He’s done it thousands of times. I’m the rookie here. Who am I to question his experience and job knowledge?”

Peer pressure is a powerful social influence. Most of us are fearful of being considered an outcast if we are the dissenter, especially if we have less informal authority than other people in our natural work group.

You may think of peer pressure as overt statements from co-workers. “Look, this is the way things are done around here.” But this is not always the case. In the scenario above, Victor did not have to remind you about his seniority and experience. It was implied and understood.