As a manager, it is likely that some of the biggest challenges you face are those that you consider to be “people problems.”

As a manager, it is likely that some of the biggest challenges you face are those that you consider to be “people problems.”

[I will not be discussing any of the myriad of technical dilemmas of managers – those that are centered on manufacturing methods, research, product development, engineering, technology, logistics, etc].

In this post, I am referring to the kinds of problems where the character of the individual is perceived to be the main reason for a performance issue. For example:

- An employee fails to follow work instructions, which results in rework.

- A worker is injured when she takes an unnecessary risk to get the job done.

- A number of employees are perpetually late when submitting expense reports.

- An employee’s timeliness in completing some assignments is unacceptable.

- Supervisors do not spend enough time talking to their employees.

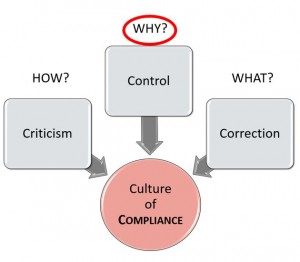

If you were faced with any of the challenges listed, what would you do? Many of us would engage the employee in some form of training, coaching, counseling, and/or expectation setting. In other words, we assume that the behavior is largely determined by the individual’s character, personality, or mindset. Unfortunately, we frequently overlook the power of “situations” in determining someone’s behavior.

A number of years ago, Stanford psychologist Lee Ross conducted a literature review on a large number of studies in psychology. He concluded that we have a tendency to ignore the situational forces that shape other people’s behavior. Ross referred to this tendency as the Fundamental Attribution Error. We make this error when we attribute people’s behavior to the way they are (their character) rather than to the situation they are in (their environment).